It is the summer of “Jaws,” and many are wondering whether 50 years is long enough for it to be safe to go back in the water again.

The classic movie, still a staple of village green summer screenings and family film nights in coastal towns everywhere, celebrates its 50th anniversary this summer.

In the film, the community that the shark terrorizes, Amity, is an island off the coast of New England, and the crowds of beachgoers are seen flooding off ferries that are unmistakably those that service Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts.

But in Peter Benchley’s debut novel, which hit bookstore shelves in 1974, the beachgoers and fodder for the book’s namesake are New York City’s summer colonists, rolling through the Hamptons on their way into Amity on Montauk Highway for summer weekends.

Benchley described Amity, through the pen of a fictional New York Times reporter covering the swimmers killed by the shark, thusly: “Amity is a summer community on the south shore of Long Island, approximately midway between Bridgehampton and East Hampton, with a wintertime population of 1,000. In the summer, the population increases to 10,000.”

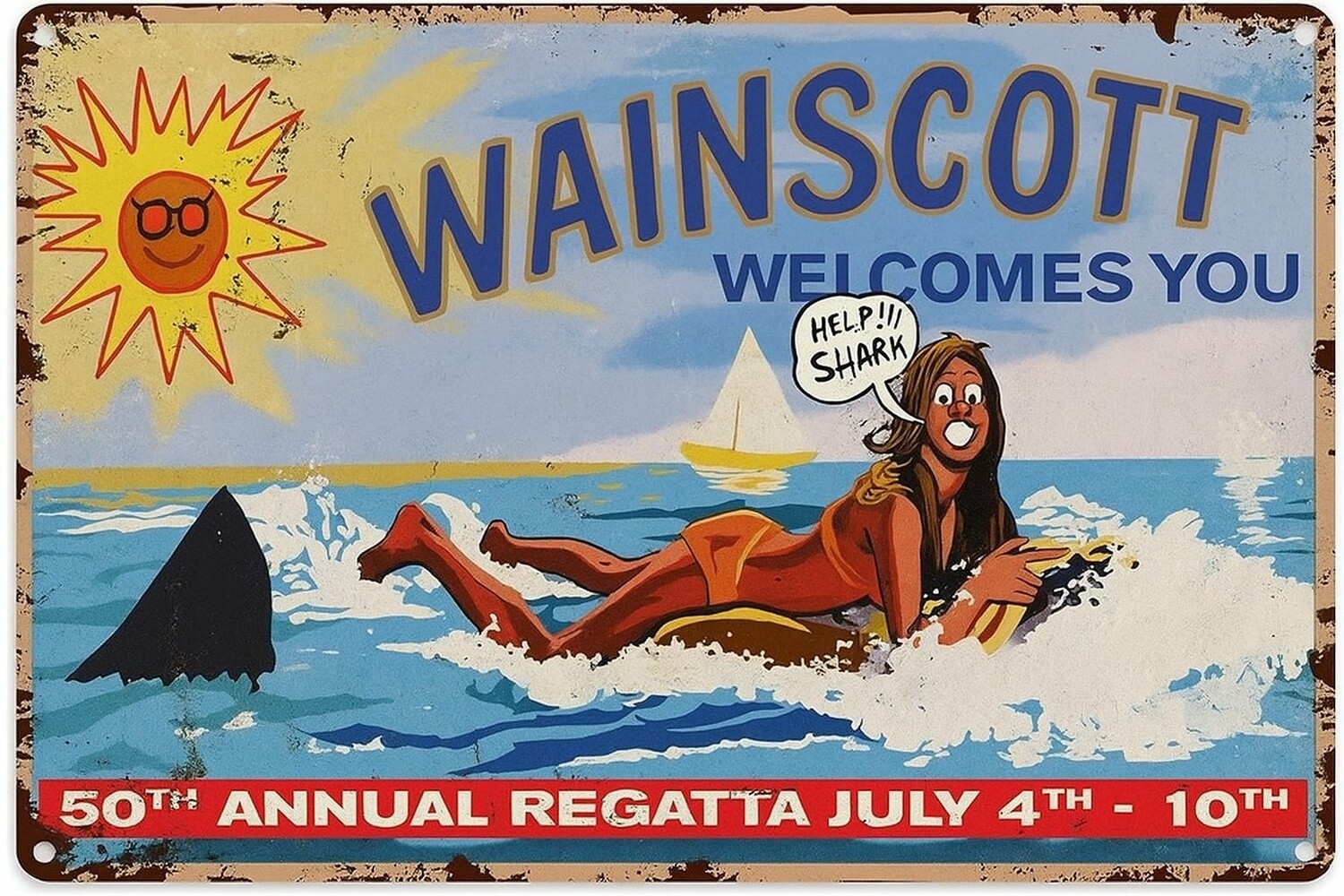

As described in the novel, the one-horse business district along the main drag between the more famous Hamptons is unmistakably Wainscott — albeit with two gas stations and a village hall.

In the book, Amity is an incorporated municipality, with a police chief and mayor, who serve as the story line’s famous protagonist and antagonist, respectively. Wainscott has none of that, of course, although an effort was made in 2020 to incorporate the hamlet as a village.

The movie has deep connections to the South Fork as well, of course, since many of its stars found their way here after soaring to stardom with the film. Chief Brody, from the movie — real name, Roy Scheider — became a beloved South Fork resident and activist. Richard Dreyfuss, who played Hooper, had a house here, too, and the film’s director, Steven Spielberg, who cemented his status as a blockbuster director with the film, still spends summers on the shores of Georgica Pond, barely a mile from where Amity would have been in Benchley’s own vision.

None of them had been here yet when they filmed “Jaws.”

Benchley had, though. The author spent summers as a kid on Nantucket, a setting much more like the one the movie ultimately adopted for presenting the story. He lived in Connecticut when he wrote the book.

But he has said the initial spark of inspiration for “Jaws” was a newspaper story from 1964 about a 4,550-pound white shark that was harpooned off Amagansett — the head of which hangs over the bar in Salivar’s in Montauk — and it was on the South Fork that he came to learn about sharks that size.

“I remember thinking at the time, Lord! What would happen if one of those monsters came into a resort community and wouldn’t go away,” Benchley wrote in his remembrance of his early contemplations of what would become “Jaws.”

That shark was brought to shore by Frank Mundus, the Montauk charter fishing captain who called himself “Monster Man” and had a knack for self-promotion accented with displaying the sharks and any other creatures of the deep he could kill, back at the dock, to drum up business for adventure-seeking city folk.

Benchley met Mundus, and spoke at length, the fisherman always said, when Benchley was crafting his novel about the murderous, shoreline-patrolling shark. The character of Quint, also a preternaturally gruff old salt, was based on him, according to Mundus.

Benchley denied it to newspapers, but few who knew the Monster Man could read Quint’s description and miss the familiarity. Robert Shaw’s portrayal of Quint seemed to essentially be an imitation of Mundus in every way, down to his affinity for preserved shark jaws, which Mundus hung from the pilings at his dock.

Quint’s boat, in the book, set sail from Promised Land, as the area now more commonly referred to as Lazy Point was long known, and within sight of the Fort Pond Bay shores where Mundus’s boat originally was docked when he moved to Montauk from New Jersey.

“My father came home one day and said he’d had a charter that day but it was only one guy and all he really wanted to do was talk about sharks and shark fishing — it was Benchley,” Pat Mundus, the charter captain’s daughter recalled. “That 4,500-pound shark, it happened exactly like he describes it in the movie: The boat broke down, they harpooned it, they had the two barrels in it and it was pulling them.”

The South Fork, with its often calm ocean beaches packed with swimmers, made for an easy place to set the novel about a shark hunting swimmers. This was not surprising, but not necessarily good news to some of those would-be swimmers on Wainscott’s beaches this week.

“I knew that Amity was here in the book, yes. It’s something you hear talked about from time to time — it’s a matter of pride,” said Richard Myers, who has lived in Wainscott for 20 years and was friends with Lorraine Gary, the actress who played Ellen Brody in the movie version. “I have never seen a shark from our beach, though.”

“I did not know that — get the heck out! I thought it was Martha’s Vineyard,” exclaimed Joe DiMona, who was sitting with his family on a recent afternoon, while kids about the age of Alex Kintner splashed in the surf nearby, when told the book was set on that very beach.

“A buddy and I actually saw ‘Jaws’ in the East Hampton movie theater when we were 15 or 16 years old. My friend said he wanted to stay for the second show so we could watch the people jump — so we stayed in our seats, illegally, for the second showing.”

Lisa Rothblum said that she had never heard of a shark being sighted from Beach Lane, where she comes daily to soak up the sun. “But if you sit here between 11:30 and 1:30 on a warm day, the whales and porpoises go right by all the time,” she said. “No sharks.”

Benchley harked in retelling about his writing of the book to having read old stories about a time when what is believed to have been a single shark — but not a white shark — attacked several swimmers along the New Jersey coastline in the 1920s.

And shark experts say that while we don’t often see larger sharks of the sort envisioned in the book swimming very near to shore here, it’s not beyond the realm of possibility.

“Just last week there was a pretty good-sized white shark that cruised past the boat of some shark fisherman who was landing a thresher shark,” said Greg Metzger, a Southampton High School marine science teacher who leads a shark research and tagging program with Stony Brook University scientists and the South Fork Natural History Museum. “They are certainly out there. The tagging data and the guys at OCEARCH has shown that there are 15-foot white sharks cruising through Long Island waters, typically in the early spring as they move north to the seal colonies and then back south again in November and December.”

The waters off our beaches have been documented to be home to juvenile white sharks as well as several species of smaller coastal sharks that readily swim just beyond the water line. Those sharks mostly feed on small fish like bunker, mackerel and bluefish or striped bass.

There has never been a documented incident of a juvenile white shark biting a swimmer, but other small sharks that bite swimmers on Long Island or in Florida do so essentially by accident, mistaking a foot or hand that flashes past them in murky water for a fleeing baitfish.

But larger sharks hunting seals are more likely to see a human form and mistake it for exactly what they are looking for.

The shores of Cape Cod and Nantucket, where thousands of seals spend their summers on sandy beaches that are often just a few feet from water deep enough to harbor large white sharks, are known for the dangers to swimmers. There have been deadly attacks and warnings are rampant — if the regular sight of large sharks swimming nearby isn’t enough deterrent.

But, Metzger says, as seal populations recover from the slaughter of decades past, they are expanding their summer territory and are already found in some places in our region year-round. One of the large adult white sharks tagged by the OCEARCH tagging program pinged in 2018 inside Gardiners Bay, not far from “the Ruins” off Gardiners Island where seals congregate in the summer.

And white shark populations are believed to be growing as well, thanks to protections enacted in the 1980s that outlawed killing them.

“We have those 8-to-10-footers that are right on the cusp of switching from eating fish, bluefish and striped bass, to seals,” he said. “The larger ones are mostly just cruising past us, unless they come upon a dead whale, but there’s not much to hold them here, because we don’t have seal colonies yet. As they expand — we will.”